In my first post, I introduced bonds as a security or investment and generally less risky than other investments, but what are they exactly?

Bonds are a type of loan. In this type of loan, the lender is called the “bond holder” and the borrower is called the “bond issuer.” Bonds are customizable, to the point where it is difficult to formally differentiate between them and other loans. One interesting feature of the bond is that the borrower decides the rate of interest, not the lender, but this might not be enough of a distinction. It turns out, however, that most bonds can be characterized by a certain interest payment structure, namely semiannual payments in arrears. These payments are collectively known as the “coupon,” from a time when physical coupons were cut from the bond certificate to be redeemed for this amount.

Like all other loans, a bond holder may sell ownership of the remaining interest payments and principal re-payment to a third party. This would be selling the bond itself. (Usually that the seller retains any interest accrued but not yet paid out. This will come up later.) In fact, most bonds that the individual investor could purchase would be sold by another bond holder, not the bond issuer. Therefore, in deciding what price to attach to a bond, the investor must consider what the interest and principal payments are worth, not to the organization borrowing the money, but to another lender.

Unlike most other loans, bonds are an arbitrary division of some larger, aggregate debt. This aggregate is the bond “issue.” Its value is definite and equal to the amount sought by the organization at some point in time. The issuer is presumably indifferent as to how this amount is divided among the bond holders, so much so that they are fine with selling the entire issue to one lender, called an underwriter, before anyone else can touch the bonds. It is the underwriter’s business to re-sell the bonds piecemeal to individual investors.

The divisible nature of bond issues requires the investor to think of the constituent bonds like bulk goods. In the same way that nuts are priced per 100 grams or per kilogram of mass at the grocery store, bonds are priced per $100 or $1,000 of issue principal. The portion of the issue quoted or traded is alternately called the “quantity” or the “par value” of the bond. Because this quantity is expressed in the same units (dollars) as cost or price, it is not possible to distinguish the two variables by units alone. For this reason, I prefer par value over quantity, since it allows the distinction to be done in a terse way: dollars and dollars par.

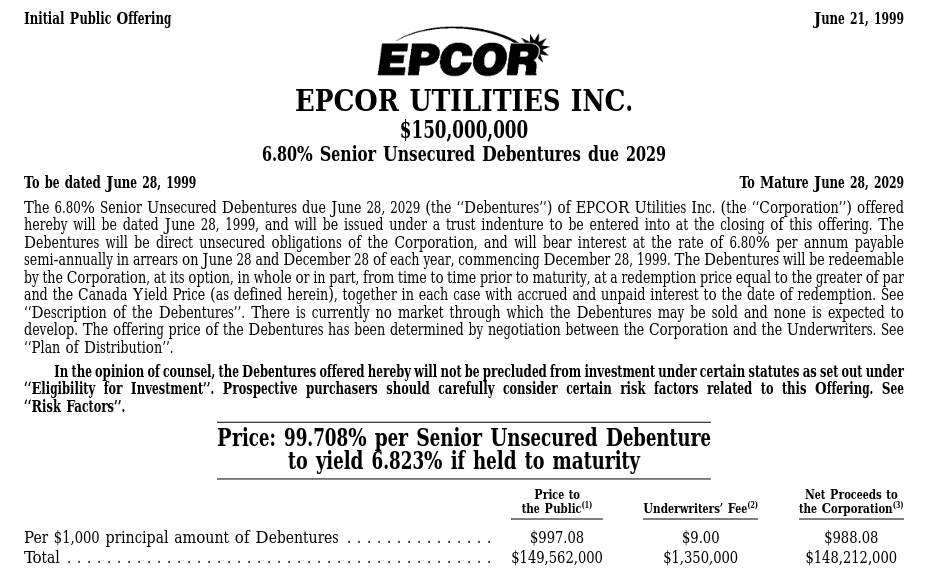

This concept is complete enough to flesh out with some real information, but before doing so, I’ll mention two important synonyms for bonds in common use: debentures and notes. The distinction between a debenture and a bond is both subtle and irrelevant to us at this point. Frankly, I’m not sure what the point of “notes” is. Consider bonds, notes and debentures to be the same thing as we go through a snippet of a bond prospectus.

A bond’s “prospectus” is the authoritative description of the terms from the bond underwriters. These documents are public knowledge. You can download them from SEDAR (https://sedarplus.ca). The above example is a ‘nice’ prospectus, since all the necessary information is contained in one document. For many other bonds, expect to go chasing supplements since the “base” prospectus contains only vague statements amounting to: ‘We may issue some bonds in the future and here are some banks that may underwrite the loan. Stay tuned.’ Luckily, our example is more concrete.

Here are the facts: EPCOR Utilities Inc. is the issuer and they seek $150 million from prospective bond holders among the public. The bonds have a garden-variety payment structure: they offer to pay a fixed annual interest rate on the debt, divided in two equal installments which are due every six months, up to and including the date the bonds mature. The annual interest rate is 6.80% and the payment dates are June and December 28. At maturity, on June 28, 2029, the $150 million will be returned to lenders along with the final interest payment. The underwriter for this issue is a syndicate comprising the investment bank divisions of CIBC, RBC and TD. If you wanted ‘dibs’ on these bonds, you bought from the banks and they were willing to sell $1,000 par for $997.08. These five items are all the information we need to describe and evaluate a garden-variety bond.

- Issuer: EPCOR Utilities Inc.

- Price: $997.08 per $1,000 par

- Annual Interest Rate: 6.80%

- Maturity: 2029-06-28

- Payment Dates: 06-28 and 12-28

For an individual investor buying bonds second hand, i.e. from another bondholder and not an underwriter, the price could be entirely different than what is in the prospectus. However, thanks to the common and therefore predictable payment structure of most bonds, we can determine what that price should be, using the other information in the list. That will be the next step.

Leave a comment